It’s improper turbine siting,” she said. “It’s not how they work, it’s where they are.”

Hobart asserted that wind turbine syndrome was a real phenomenon.

“Every time we go away, we get better,” she said. “It’s a disease, we’ve been given it, and we can cure it—by going away.”

Hobart accused town officials of allowing “politics, money, and self-interest” to interfere with protecting the health and safety of Falmouth citizens, and said firms like Vestas “hide behind the big green picture.”

·

—Conor Powers-Smith, Falmouth Patch (6/7/11)

At a special meeting on Monday night, held at the auditorium of the Morse Pond School to accommodate what was expected to be a large crowd, the Board of Selectmen heard from scientists, engineers, state legislators and their representatives, and Falmouth citizens concerning the contentious issue of wind turbines, specifically the Wind 1 and Wind 2 turbines located at the town’s Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Moderated by Nancy Farrell, the meeting played out before a packed room, which included many of the turbines’ residential abutters—a number of whom who have complained of a variety of health and quality of life issues since the first turbine went into operation.

The first speaker, Steven Clark of the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, appeared representing the Deval Patrick administration. Clark voiced Governor Patrick’s commitment to wind and other alternative energy sources, and said Falmouth’s approach was “right in line” with the administration’s policy, and promised that “the state will continue to be involved and provide leadership as needed going forward.”

The board next heard from Gail Harkness, chairman of the Board of Health, who summarized the suite of health issues cited by abutters of the turbines. Among many such issues, which some have collectively called “wind turbine syndrome,” are headaches, vertigo, anxiety, sleeplessness, and nausea.

Harkness presented the steps the Board of Health had taken in response to the complaints, including the establishment of an online database of articles dealing with turbine-related health concerns from around the world, the creation of a complaint/comment form used to gather information from residents about their health issues, and repeated visits to the area in varying weather conditions.

Christopher Menge, an engineer with Harris Miller Miller and Hanson Inc., the firm Falmouth hired to conduct a study of noise at the turbine site, summarized that report’s findings. The sound samples, taken over the course of 10 days in June 2010, were measured against the background noise in the area, as is standard in determining whether a particular source of sound exceeds the maximum allowable levels set by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection.

That threshold is 10 decibels over background noise, and Menge said the study had found that the turbine noise could approach or exceed that limit late at night or early in the morning, when the lack of cars, singing birds, and other activity means that background noise is at its lowest. Menge insisted that the greatest problems would occur when wind speeds were low, and unable to mask the sound of the turbine.

Those findings were directly contradicted by the next speaker, Todd Drummey, who lives on Blacksmith Shop Road near the site of the turbines. Like most nearby residents, Drummey maintained that the disturbance was greatest at just the opposite extreme.

“It’s annoying at low speeds,” Drummey said. “It’s intolerable at high speeds. It drives people out of their houses.”

Drummey went on to call the HMMH report into question, saying that artificially low wind shear variables had been used, invalidating the model. He also said that the study had been conducted during nights of low wind, and no data from times of higher winds had been gathered.

Michael Bahtiarian of Noise Control Engineering, Inc., the firm contracted privately by a group of abutters, presented his own findings concerning what he called “aerodynamic amplitude modulation,” which he defined as “the swishing noise” the turbines are known for. Bahtiarian said that, while MassDEP regulations are based on hourly averages, within a single minute the noise from the turbines can fluctuate widely, often exceeding the 10-decibel allowance. Also, the fluctuation itself could be an irritant.

“It’s not only the level, it’s the fluctuation of the sound,” he said.

Asked by Selectman Frietag whether sound barriers similar to those used alongside busy highways could mitigate the noise from the turbines, Bahtiarian said, “Your barriers would need to be nearly as high as your turbine, or nearly as high as your house.”

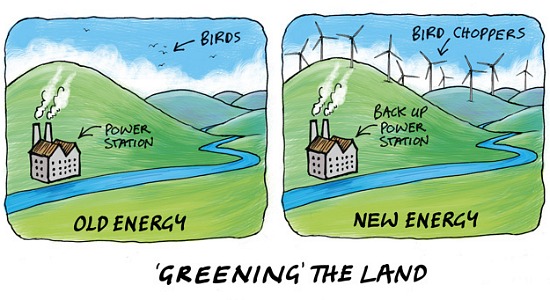

Representatives of Weston & Sampson and Vestas, the consulting and engineering firms which sited and built the turbines, said there was no evidence that the devices’ noise exceeded allowable levels, and urged the board to consider the revenue lost by curtailing the turbines’ use. Currently, the Wind 1 turbine is shut down in wind speeds in excess of 10 meters per second.

Thomas Mills of Vestas said this was exactly the opposite strategy the town should be pursuing, and recommended shutting down the turbines in lower wind conditions, in line with the HMMH study’s findings that this is when their noise rises highest above background levels.

Malcolm Donald, another resident, showed videos depicting light flicker, the strobe-like effect caused by the continuous blocking and unblocking of sunlight.

“The inside of the house looks like a disco in the mornings,” he said.

Donald went on to assert that the town had originally approached General Electric to construct the turbines, but that the company had turned those plans down due to its safety guidelines, which call for a significantly larger setback area than those of Vestas. Due to the possibilities of the turbines flinging shards of ice in cold conditions, and of the blades themselves flying away from the turbines in the event of a catastrophic mechanical failure, said Donald, GE considered many of the homes around the facility, a stretch of Route 28, and the wastewater plant itself, to fall inside the minimum safe distance.

Susan Hobart, another resident of the area, blamed Vestas’, and the town’s, shorter setback-distance standards for the problems with the turbines.

“It’s improper turbine siting,” she said. “It’s not how they work, it’s where they are.”

Hobart asserted that wind turbine syndrome was a real phenomenon.

“Every time we go away, we get better,” she said. “It’s a disease, we’ve been given it, and we can cure it, by going away.”

Hobart accused town officials of allowing “politics, money, and self-interest” to interfere with protecting the health and safety of Falmouth citizens, and said firms like Vestas “hide behind the big green picture.”

More abutters came forward to tell the board about their experiences with the turbines. Opinion was strongly and universally against the machines as currently sited.

Barry Funfar said, “I can no longer stand even the sight of these out-of-place monoliths,” and urged the town to “take the things down while you can still resell them.”

Terri Drummey referred to the turbine issues as “the so-called Falmouth Effect,” and described the difficulty sleeping and concentrating which she said had led to her 10-year-old son’s declining grades, as well as her daughter’s headaches, and the ringing in her husband’s ears.

“We are the unwilling guinea pigs in your experiment with wind energy,” she said.

The board is scheduled to hear further testimony from those affected by the turbines at its July 11 meeting.